The Queen’s Gambit – Ep 1: Openings

SPOILERS AHEAD

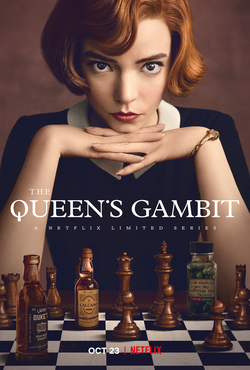

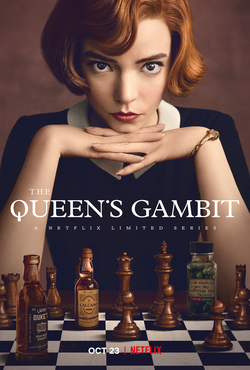

My daughter Amber recommended The Queen’s Gambit (Netflix) to me because she knows I loved the period piece “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” and am a chess nut. Good call on her part. After watching Episode One “Openings” I thought I might write a series of reviews of the show discussing its use of story devices and comparing it to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey.

The Prologue

Episode one opens with Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) waking up, dressing while someone rustles in the bed, taking some pills, rushing from her hotel room, and bursting into a chess match for which she is late. A gaggle of reporters are taking flash photos of her as she shakes her opponent’s hand (an annoyed middle-aged white man) and apologizes profusely for being late. Then, as the chess clock ticks, we flashback to her childhood.

A lot happens in this opening. It establishes our hero as a chess celebrity, a drug abuser, somewhat promiscuous, and possibly under some sort of chess trial. This man is apparently important and she is very differential to him. It sets up a bunch of questions in our minds (who is this woman, who is this man, why is she taking pills, what is the nature of this chess match?) This is a teaser and leads us into the backstory of our hero. It might also be considered a proper prologue setting us up for the main story.

The Ordinary World

As our story begins, we meet young Beth (Isla Johnston) as a nine-year-old child at the scene of a car crash which kills her mother. She’s taken to an orphanage (they assume the father is previously dead) where she’s given a nice cot and meets the folks who will be taking care of her as well as some other orphans – one in particular is Jolene (Moses Ingram).

This is clearly a period piece as all the cars are 1940s style and the police uniform is from the same era. This shot is designed to set the stage for our hero’s Ordinary World.

Jolene is Beth’s first mentor. The mentor character is typically the one who helps the hero understand their new situation or Special World. Jolene explains that the pills she’s given will make her “feel good” and not to overuse them. Jolene also notices the effects of withdrawal when Beth stops taking the pills, and explains that as older children, they’re likely “lifers” at the orphanage. Jolene is not so much a mentor as an “expositioner.”

This is an interesting device since we’re actually being introduced to Beth’s Ordinary World by showing her walking into a new situation after having lost her mother (notice how often heroes are orphans – especially in Disney tales). We see this displacement often in storytelling – it creates a fish out of water effect. Mind you, this is not the Special World of the story – but just the baseline world our story is taking place in. By having Beth enter a new situation in the opening of the story, she needs Jolene to explain everything to her – and to the viewers as well. Soon, Beth will cross over into the actual Special World of competitive chess.

You might compare this to Karate Kid (1984) where young Daniel has just moved from New Jersey to California with his mother to start a new life. It’s not the Special World of the story – but allows us to get a lot of backstory because he’s the new kid in town. In Daniel’s case the Special World is that of competitive karate.

We also see a bit of foreshadowing in the form of the drugs the orphanage staff feed the children. All the children are given green pills (the same green pills we see in the opening scene of episode one).

Next, we’re treated to a flashback as Beth remembers her mother burning books and pictures after her father tries to convince mother Mary to come home with him. We see Beth clutch her mother’s bound dissertation on mathematics. Then, we see tear-streaked Mary looking in the car’s rear view mirror saying “I’m sorry” to this younger Beth.

This is classic backstory exposition. It implies mother Mary is a math genius and that she may have some emotional or mental health issues – possibly setting up the mystery of how the accident occurred. Both of these are foreshadowings of Beth’s drug abuse and genius-level chess abilities.

The Call to Adventure and the Refusal of the Call

Beth is given the task of cleaning the teacher’s erasers and goes to the basement to do so. There, she sees the janitor Mr. Shaibel playing chess alone. Beth has never seen chess and demands to be told what it is – Shaibel refuses and sends her away.

Here, the “call” is the chess board reaching out to Beth and capturing her interest. It’s also a “call” to the mentor. And in a twist to the classic monomyth, it is the mentor who refuses the call to adventure. He sends the hero away. And she must return to make the mentor take up the challenge to train her.

This also calls back to the “reluctant mentor” we see in Karate Kid. Mr. Miyagi is approached by Daniel to teach him karate, and Miyagi refuses. (When the teacher is ready, the student will come.) This is also Beth’s introduction to the Special World. Mr. Shaibel is her new mentor and he will guide her into the Special World of competitive chess.

The Meeting with the Mentor

That night, we see Beth wrestling with her thoughts and she takes some of the green pills she’s been palming. While in bed she imagines the chess board on the ceiling. The next day she returns to Shaibel’s basement and explains that she understood what she saw (this piece moves like this, that one like that. “You learned all that from watching me?”) and now the mentor is interested. Shaibel gruffly allows her to sit at the board and he begins playing her – but he always plays the white pieces. Eventually, he gives her his personal copy of “Modern Chess Openings” and allows her to alternate playing both black and white pieces.

Beth has become indoctrinated into competitive chess and Shaibel has recognized her genius. He accepts her as an apt pupil and comes to realize she is worthy of his mentorship. As mentors do, he is passing on his wisdom and gives her a personal gift that will allow her to traverse the Special World. Compare this to Obi Wan Kenobi’s gift of the lightsaber to Luke Skywalker and taking Luke on as a student of the Jedi way.

Crossing the First Threshold

Later, she is introduced to Shaibel’s friend – Mr. Ganz, the head of the chess team at the local high school. He challenges Beth and loses with Beth predicting “mate in three.” We also see Beth beat both men at simultaneous chess. Beth even leaves the table, calling out her final moves destroying Ganz without looking. Ganz arranges for Beth to play simultaneous chess against the boys on his chess team. She wins all the matches with ease. She relates to Shaibel how poorly the boys played and how surprised she was at how easily defeated they were.

Beth has crossed the first threshold – she’s met her first adversaries and conquered them. Now, she will have more trials and new oppositional forces.

We’re also seeing something terribly important, subtle, and necessary in this story – the education of the audience in chess terminology. In order for the viewer to understand how gifted Beth is, we must be told enough about the game so that we can appreciate it when Beth does well – or perhaps later when she fails.

We can see this in such movies as Top Gun (1986) – where Maverick evades and defeats his opponent by performing a maneuver that causes the enemy to fly past him. This is critical in the climax of the film where Maverick saves his buddy using the same technique. In both cases, it’s imperative that the audience have a basic understanding of the hero’s prowess so that we can appreciate it later. To do this, the storyteller must interweave education of the audience with the hero’s journey.

Note that one of the openings Shaibel teaches Beth is the titular Queen’s Gambit. I have no doubt we’ll see this mentioned again and it will likely be critical to the story’s climax (see Chekov’s Gun).

The Missing Inner Quality

In the final scene, Beth is watching a movie with her fellow orphans and sneaks away to steal a screwdriver from Shaibel’s toolbox. She unscrews the lock to the infirmary and takes a giant jar of the green tranquilizer pills. She gulps down a handful of them. As she turns to escape with the jar in her arms, her teachers and friends all find her standing on the chair caught red-handed. She succumbs to the overdose of pills muttering “Mom?” as she passes out and falls to the floor, dropping the jar which shatters and floods the room with the pills.

This scene does double-duty. It exposes Beth’s missing inner qualities – drug addiction and the loss of her mother – and provides a cliffhanger so we’ll tune in next week.

These missing inner qualities of Beth’s are the true essence of this story. Beth will have an outer journey as she becomes a chess master. But she will also have an inner journey as she overcomes her drug addiction and comes to grips with her tragic loss. Hero’s journeys are always two-pronged: the outer tangible goal and the missing inner quality. The hero may or may not achieve the outer goal, it really doesn’t matter. But for the audience to achieve catharsis, the inner missing quality must be resolved.

This is a classic cliffhanger. We will tune in next week to see how Beth survives this – we know she will since we saw her in the future during the prologue. I’ll be here next week to look at more structure and story of “The Queen’s Gambit.”